Why You Should Sample and Test New Oil

Recently, I have visited several plants with oil analysis programs that have ranged from non-existent to fairly robust. The common problem in all of them was that there was no sampling or testing of new oil receipts. This is critical for several reasons, such as to ensure that the oil received is the oil ordered, to establish a baseline for subsequent testing and monitoring of the oil condition, and simply to verify lubricant cleanliness. It is essential to fully understand each of these important issues.

Ensuring the Lubricant Received is the Lubricant Ordered

This may involve a simple viscosity comparison or a complete elemental analysis to ensure that the additive package meets the application’s requirements. At the very minimum, a viscosity comparison should be performed.

In his “Should New Lubricant Deliveries be Tested?” article for Machinery Lubrication, Jim Fitch references an audit performed by the American Petroleum Institute (API) in which 562 motor oils were tested. The results were as follows:

4 percent of the motor oils were classified as having standard deviations (one out of every 25 oils tested). Many had the wrong concentration of additives, while others failed to meet low-temperature specifications.

16 percent were classified as having marginal deviations (one out of every six oils tested).

Assuredly, technology has advanced since this study in 2001, but as the article explains, “Lubricants are blended by humans. They are inspected by humans. They are transported and packaged by humans. They are labeled by humans. When it comes to humans, there is one inalterable constant - we make mistakes.”

It has been said that the industrial world rides on a lubricant film between 1 and 10 microns. This film thickness is determined by the speed of rotation, the load on the elements and the lubricant’s viscosity. Lubricants are purchased with a specific viscosity to maintain that lubricant film and eliminate boundary conditions or metal-on-metal contact for the particular application. While this applies for lubricants purchased in drums, buckets, bottles, etc., in the case of bulk deliveries, there is an additional consideration.

A delivery truck generally has tanks or containers of different sizes and is loaded based on the delivery schedule. For example, the truck may have four compartments: a 7,500-gallon compartment, a 5,000-gallon compartment and two 2,500-gallon compartments. The orders being delivered today may require 7,000 gallons of oil “A,” 4,000 gallons of oil “B,” 2,000 gallons of oil “C” and 1,500 gallons of oil “D.” Tomorrow’s deliveries may require 6,700 gallons of oil “D,” 4,000 gallons of oil “C,” 1,200 gallons of oil “A” and 1,000 gallons of oil “B”. With this type of delivery schedule, cross-contamination is going to occur. Therefore, you should ask your supplier if each truck is cleaned prior to loading for the next trip. Also, find out if the loading and unloading hoses are cleaned. Remember, it is much less expensive to sample and test oil than it is to repair a failure and suffer the costs of downtime associated with that failure.

5 Tips for Setting Target Cleanliness Levels

- Set targets for all lubricating oils and hydraulic fluids.

- Use vendor specifications as ceiling levels only.

- Set life-extension (benefit-driven) targets.

- Consider the machine design, application and operating influences.

- Make it a personal decision because you as the machine owner are the one paying the cost of failure, not the machine supplier, oil supplier, filter supplier, bearing supplier or oil analysis lab.

If the potential exists for lubricants to be mislabeled or contaminated and you are not currently taking steps to prevent this unknown and untested lubricant from contaminating your lubricants, you are in effect playing Russian roulette with your machines. Even if you have been lucky so far, eventually you will find the chamber with the live round. New lubricants should be tested upon receipt and placed in quarantine until they are verified to be the correct lubricants. Once acceptable results come back from the lab, these lubricants should then be labeled as satisfactory and placed into storage.

Establishing a Baseline for Subsequent Testing and Monitoring

In order to conduct accurate lubricant condition monitoring, a baseline sample should be taken. This will allow subsequent tests to be compared to the baseline test when the lubricant was new. After all, if you have no idea where you started, how can you tell where you are going? Once this baseline sample has been obtained, it should be kept as a reference. You can then directly compare the lubricant’s color or smell to that of the baseline sample. This will provide an immediate indication if there is a problem with the lubricant in your machines.

Verifying Lubricant Cleanliness

Several studies indicate that the cost of excluding a gram of dirt is only about 10 percent of what it will cost once it gets into your lubricants. In some cases, when new oils from major manufacturers were tested, the ISO cleanliness codes have ranged from 14/11 (pretty good) to 23/20 (not good at all). The average of these samples was 19/16, and several were 20/18 or 21/18.

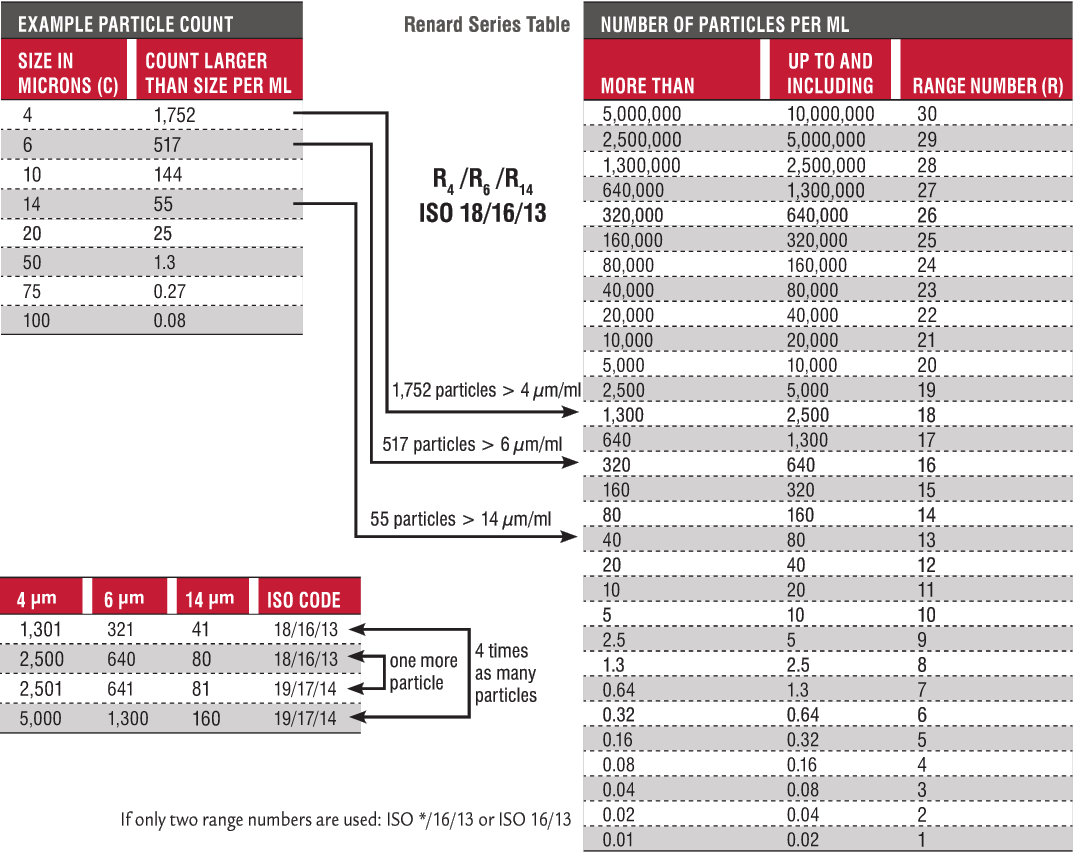

For those who may not understand ISO cleanliness codes, they refer to values on a Renard series table in conjunction with particle counts of a specific micron size. For instance, in a two-digit ISO cleanliness code, particles of 4 and 6 microns are counted. A corresponding value is then assigned based on the number of particles of a specified size and where they fall on the table.

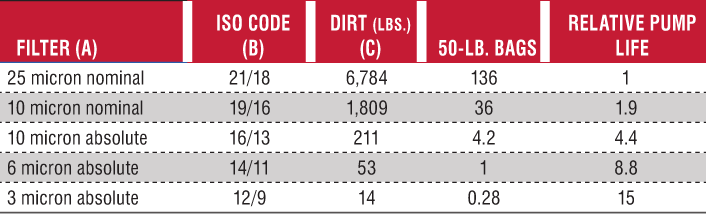

As you can see from the illustration above, there is a significant difference in particle counts between a code of 14/11 and 23/20. Keep in mind that these numbers are for packaged lubricants. For bulk deliveries, the numbers are much worse, running from 20/17 to 28/21. To get a better understanding of what this means, consider that a 50-gallon-per-minute pump moving a lubricant with an ISO code of 21/18 will pump approximately 6,784 pounds of dirt in a year.

In addition, it has been estimated that one particle of dirt has the potential to generate six wear particles. Particles in the 4- and 6-micron range are most damaging to your equipment because they are the same size as your lubricant film.

Of course, someone has to pay to remove this dirt from the lubricants. You can do it, or you can work with your vendor and split the cost. You may even be able to get your supplier to deliver lubricants that meet your cleanliness targets. This is something you should take into account when your supplier contract comes up for rebidding.

If you are not presently tracking lubricant cleanliness, hopefully this will prompt you to start. If you are tracking cleanliness but are not sampling your oil upon receipt, you are spending good money to clean up someone else’s mess. Ideally, you can work with your lubricant supplier and come up with cleanliness targets that make sense.