Juggling Systematic Gap Reduction within Lubricant Handling

While all six Lubricant Lifecycle Stages within The Ascend Chart play a significant role inside program ownership, one that specifically stands out with regard to site improvement and systematic gap reduction is Lubricant Handling and Application.

While all six Lubricant Lifecycle Stages within The Ascend Chart play a significant role inside program ownership, one that specifically stands out with regard to site improvement and systematic gap reduction is Lubricant Handling and Application.

The Lubricant Handling and Application (H) section is unique in that it is heavily involved in the lubricant’s “cradle-to-grave” process and frequently relies on on-site employee engagement and interaction. Since this is the case, it is vital to understand, identify, optimize and maintain for overall lubrication program development.

But what exactly should the Lubricant Handling and Application aspects of the lubrication program encompass? As we begin to look at this Lifecycle Stage, we will go through the three tiers, called levels, that structure the chart and each of the specific factors that are necessary to be evaluated and augmented.

But what exactly should the Lubricant Handling and Application aspects of the lubrication program encompass? As we begin to look at this Lifecycle Stage, we will go through the three tiers, called levels, that structure the chart and each of the specific factors that are necessary to be evaluated and augmented.

Platform Level

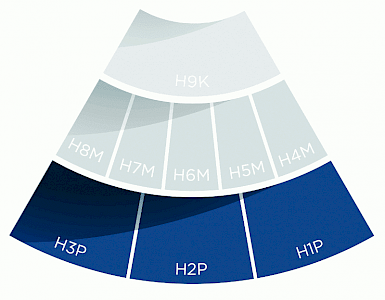

Upon reviewing each level, we initially take a look at the first and broadest level of ownership, known as the Platform level. The collection of factors at the Platform Level across all Lifecycle Stages is the foundation upon which the lubrication program is executed. For those within the Lubricant Handling and Application Stage, it encompasses all activities actually being completed on the plant floor itself and can be referred to as the “boots on the ground” tier. Specific factors to discuss in this section are Lubricant Application Tasks (H1P), Machinery Configuration (H2P) and Lubricant Handling and Application Devices (H3P).

The effectiveness with which Lubricant Application Tasks (H1P) are carried out on the plant floor plays a direct role with regard to asset reliability. These tasks should always consider three fundamental parts:

The effectiveness with which Lubricant Application Tasks (H1P) are carried out on the plant floor plays a direct role with regard to asset reliability. These tasks should always consider three fundamental parts:

- The safety of the individual performing the job

- The ergonomics of the job being completed aids in the maintainability of the asset

- The desired ORS (Optimum Reference State) of the asset

Application tasks should be designed so that there is limited exposure of the lubricant to the environment while supplementing reliability. Common examples of lubricant application tasks could include oil and grease replenishment, lubricant changeouts, lubricant flushing as well as periodic lubricant hardware replacement in the form of breathers, filters and other miscellaneous consumables. Each of these specific lubrication tasks should have detailed work instructions or procedures with precise allocated time requirements including logistics that help continue to drive the standardization and optimization of work orders. As with most other plant floor activities, the training, coaching and assessment of lubricant application tasks should be carried out systematically and revised over time.

The proper Machine Configuration (H2P) for lubrication-specific needs at a site is something that is almost always overlooked upon initial installation. Site personnel tasked with the integration and installation of new equipment are often challenged, and rightly so, by cost control measures. While the concept of this practice seems ideal, this can be somewhat myopic in nature if not fully understood. Often only the initial purchase cost is considered, rather than the entire life-cycle cost of the asset. EEM (Early Equipment Maintenance) and FMEA (Failure Modes and Effects Analysis) strategies should be reviewed and a MOC (Management of Change) process should be implemented to standardize and enhance asset configuration based on reliability, safety, and ergonomics.

It is fairly common to see established lubricant dryness and cleanliness reliability goals for all lubricated assets made visible through oil analysis. While this is great practice, the same level of thought and detail should be considered and executed during the lubricant handling process from storage to the asset itself. Poor Lubricant Handling and Application Devices (H3P) create an unsolicited opportunity for contamination that may compromise the integrity of the lubricant prior to it ever entering the asset. Understanding this challenge—what the process looks like, what variables must be considered and how it can directly affect the reliability of the asset—play an imperative role in the uptime of equipment.

Management Level

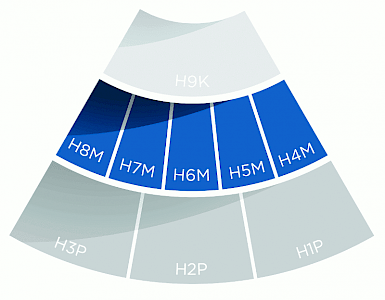

After reviewing the previous Platform Level regarding actual work being completed on lubricated assets and components in the field, we now need to turn our attention to the management of these workings. The Management Level is necessary when providing direction towards lubrication excellence as it works to strive for the fulfillment of an organizational goals and objectives. Specific Factors to discuss in this section are Lubrication Program Management (H4M), Lubrication Routes (H5M), Machinery Inspection Tools and Practices (H6M), Goals and Reward Systems (H7M), and Lubricant Handling and Application Training (H8M).

After reviewing the previous Platform Level regarding actual work being completed on lubricated assets and components in the field, we now need to turn our attention to the management of these workings. The Management Level is necessary when providing direction towards lubrication excellence as it works to strive for the fulfillment of an organizational goals and objectives. Specific Factors to discuss in this section are Lubrication Program Management (H4M), Lubrication Routes (H5M), Machinery Inspection Tools and Practices (H6M), Goals and Reward Systems (H7M), and Lubricant Handling and Application Training (H8M).

All lubrication activities should be managed in such a way that past, present and future tasks can be scheduled, monitored, controlled and executed as required. The utilization of management software also aids in the understanding of the site’s lubricated assets as well as all of the specific lubrication points included within the program. It is important to understand the holistic functionality of the management software and the integration opportunities available between it and the site’s CMMS (Computer Maintenance Management System). Failing to utilize an electronic tool for Lubrication Program Management (H4M) makes it extremely difficult to dynamically perform these tasks and can put the site at risk for tasks being performed at the wrong frequency or not at all.

We have covered lubrication-specific tasks in detail and now will begin to take a look at grouping these tasks together in the form of Lubrication Routes (H5M) to be completed through work orders. The routes themselves provide logic to the planning and execution of these tasks over time all while allowing feedback of the lubrication program as a whole.

Route development should be well thought out, organized and logistically reasonable to optimize the time available for individuals to perform them. Routes can be build based on lubricant type, task frequency, plant floor location and machine serviceability among other influencing variables. While it is ideal to establish lubrication routes and minimize changes, some deviation is necessary from time to time. It is ideal to structure a system such that it lends itself to be dynamically changed based on workload and resources availability. Also, it’s worthwhile to consider reviewing lubrication routes on an annual or biannual basis. This should be done by individuals across the program from scheduling to execution to optimize frequencies and stay in alignment with other continuous improvement practices.

The inspection of assets with regards to your lubrication program is often a practice that is executed but in an abbreviated manner. Machine Inspection Tools and Practices (H6M), while somewhat time-intensive, can be extremely productive when performed properly. Knowing specifically where and how to look, having a keen eye on what is considered abnormal and understanding what troubleshooting detail to report can provide pivotal information when avoiding a failure. Much like lubrication tasks, inspections work best when standardized and carried out in detail. All lubrication inspections on-site should have detailed work instructions of the who, what, where, when and why.

While often overlooked, Goals and Reward Systems (H7M) have their place in reliability as well. If individuals involved in the lubrication program do not have clear objectives, complacency can set in even among the best employees. As plants begin to build upon or reinvent their lubrication programs, one of the initial steps should be identifying site role models to recruit into the program, establish long-term goals and further identify more granular short-term goals needed to complete long-term ones. Rewards for meeting and exceeding goals within the program offer incentives to do the right thing, even when no one is looking. While monetary incentives are considered to be a quick motivational tool, there are other rewards that can possibly yield even better long-term results. Augmenting the morale of the site can be accomplished through the visual awareness of program improvements on small team project wins via bulletin boards, newsletters and lunch-and-learns. Changing the culture from a “firefighting mentality” through reliability advancements in lubrication yields lasting results that create a sense of pride in the organization for years to come.

While often overlooked, Goals and Reward Systems (H7M) have their place in reliability as well. If individuals involved in the lubrication program do not have clear objectives, complacency can set in even among the best employees. As plants begin to build upon or reinvent their lubrication programs, one of the initial steps should be identifying site role models to recruit into the program, establish long-term goals and further identify more granular short-term goals needed to complete long-term ones. Rewards for meeting and exceeding goals within the program offer incentives to do the right thing, even when no one is looking. While monetary incentives are considered to be a quick motivational tool, there are other rewards that can possibly yield even better long-term results. Augmenting the morale of the site can be accomplished through the visual awareness of program improvements on small team project wins via bulletin boards, newsletters and lunch-and-learns. Changing the culture from a “firefighting mentality” through reliability advancements in lubrication yields lasting results that create a sense of pride in the organization for years to come.

It is common to see lubrication handling and application tasks being performed in the plant-based solely on the knowledge handed down over the years through apprenticeship. While the utilization of site knowledge is invaluable, formal education and training in the field and classroom should be coupled with this experience to reach lubrication excellence. Understanding the role lubrication plays in equipment uptime, properly training individuals on best practice versus traditional practice and establishing a Lubricant Handling and Application Training (H8M) plan to correct these poor practices drives the standard of expectations.

This execution can be correlated to the process of learning to swing a golf club. Most untrained newcomers to the sport will likely develop poor techniques early on. Bringing in a trainer can help combat these bad habits. One of the first things a trainer will focus on is the proper technique of a structured swing. Through repetition over time, the golfer develops the proper swing pattern, which leads to better overall performance. Training in the workplace works in much the same way. This progression generally results in some retraining of experienced individuals in troubled areas and minimizes the concern that poor practices may be passed on to newer individuals during the onboarding. Identifying proper technique and understanding the benefit of correct lubrication practices sets the tone for a more reliable tomorrow.

Key Performance Indicator Level

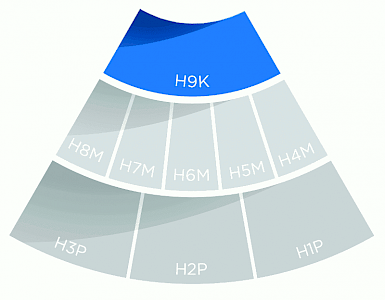

By now we should have a sound understanding on the importance of the groundwork laid during the Platform level as well as the ownership involved during the Management level. The final level, Key Performance Indicators (KPIs), aids in qualifying investment or focus on an area of the process. Some key aspects of launching new KPIs are:

By now we should have a sound understanding on the importance of the groundwork laid during the Platform level as well as the ownership involved during the Management level. The final level, Key Performance Indicators (KPIs), aids in qualifying investment or focus on an area of the process. Some key aspects of launching new KPIs are:

- Data should be easily attainable

- KPIs should be agreed upon by the majority of stakeholders in the program

- KPIs should have standardized update frequencies

During the initial development or revitalization of a lubrication program, there should only be a few sound KPIs established. As the program advances, the KPIs should advance as well.

The Lubricant Handling and Application KPIs (H9K) provide an intermittent measurement of each of the factors mentioned above in the Platform and Management levels. The completion of tasks, performance of tasks and inspection, and the systematic evaluation of a lubricant handling training plan are just a few examples of popular metrics associated with this particular factor. Focusing on these specific values aids in driving the overall lubrication program effectiveness.

Conclusion

After reviewing the intricate details of the Lubricant Handling and Application Lifecycle Stage, it should be abundantly clear why this aspect is imperative when striving for lubrication excellence. Understanding the importance and need for each of the three Levels, as well as what goes into properly classifying the Factors included involved in each Level, safeguards the holistic program integration and leads to a clean, “well-oiled” and optimized lubrication and reliability program.